03 nov. 2021Curating the Meaningful Museum

Consider for a moment your most memorable museum experience. Where were you? Who were you with? Why were you in the museum? And finally, what made the experience meaningful such that it remains with you until this day?

Museums change us, this much is certain. Personal memories aside, research in visitor psychology and cultural mediation have long suggested that museums are spaces of meaning-making, lauding them as potent forces for social progress, intellectual advancement, and personal transformation. There is, however, a flipside to this ardent idealism. For as many edifying recollections as the thought exercise above may produce, there nevertheless exists a discernible thread of negative experiences common to many visitors. Museum memories that undermine the institution and its mandates, replete with disappointment, boredom, and even social injustice, also result in the creation of meaning. Museums may change us, but change is not always a good thing.

New museology

The quest to understand the mechanisms of meaning in museums has important implications for fields as diverse as art history, museum studies, the psychology of aesthetics, and cultural informatics. However, perhaps most importantly, museum meaning directly implicates the various publics that frequent museums (as well as those who don’t). Indeed, museums do not create meaning in a vacuum, but rather depend on the visiting public in order to engage, advance, and ultimately realise their educational and social missions. More than merely repositories of art and cultural heritage, museums have increasingly embraced new roles as intersectional spaces and community hubs. This conceptual shift from passive to participatory has not appeared overnight, but rather is a reflection of what some have termed the new museology, that is to say, an eschewing of the museum’s former reputation as a highly privileged and academic space in favour of a more inclusive, experiential, and even entertainment-oriented focus.

Museums are playing catch up in a world of digital transformation, sociopolitical unrest, unabated climate change, and public health crises. Now more than ever, understanding what makes the museum meaningful is essential. In a recent New York Times piece entitled 10 Ways for Museums to Survive and Thrive in a Post-Covid World, Jason Farago argued “when the old habits get washed away, knowing what you stand for matters.” Extending beyond the limited frame of museum collections and into the deeper complexities of the visit itself, my colleagues and I at the University of Luxembourg Human-Computer Interaction Research Group set out to identify precisely how meaning happens in museums, and how we might apply this to enhance the museum visitor experience.

Memorable museum experiences

Building on the work of John Falk and Lynn Dierking, who argue that memories act as a kind of archive of what is personally meaningful to us, we collected over 500 memorable museum experiences from visitors around the world. This included every type of museum ranging from art, science, natural history, and heritage sites, among others. We analysed the data thematically, paying close attention to patterns of experiences that resulted in a museum visit becoming memorable. Altogether we identified 23 phenomena in and around museum spaces that led to a sense of personal meaning. We refer to these phenomena as triggers. For example, consider the following experience at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City that implicated a number of triggers.

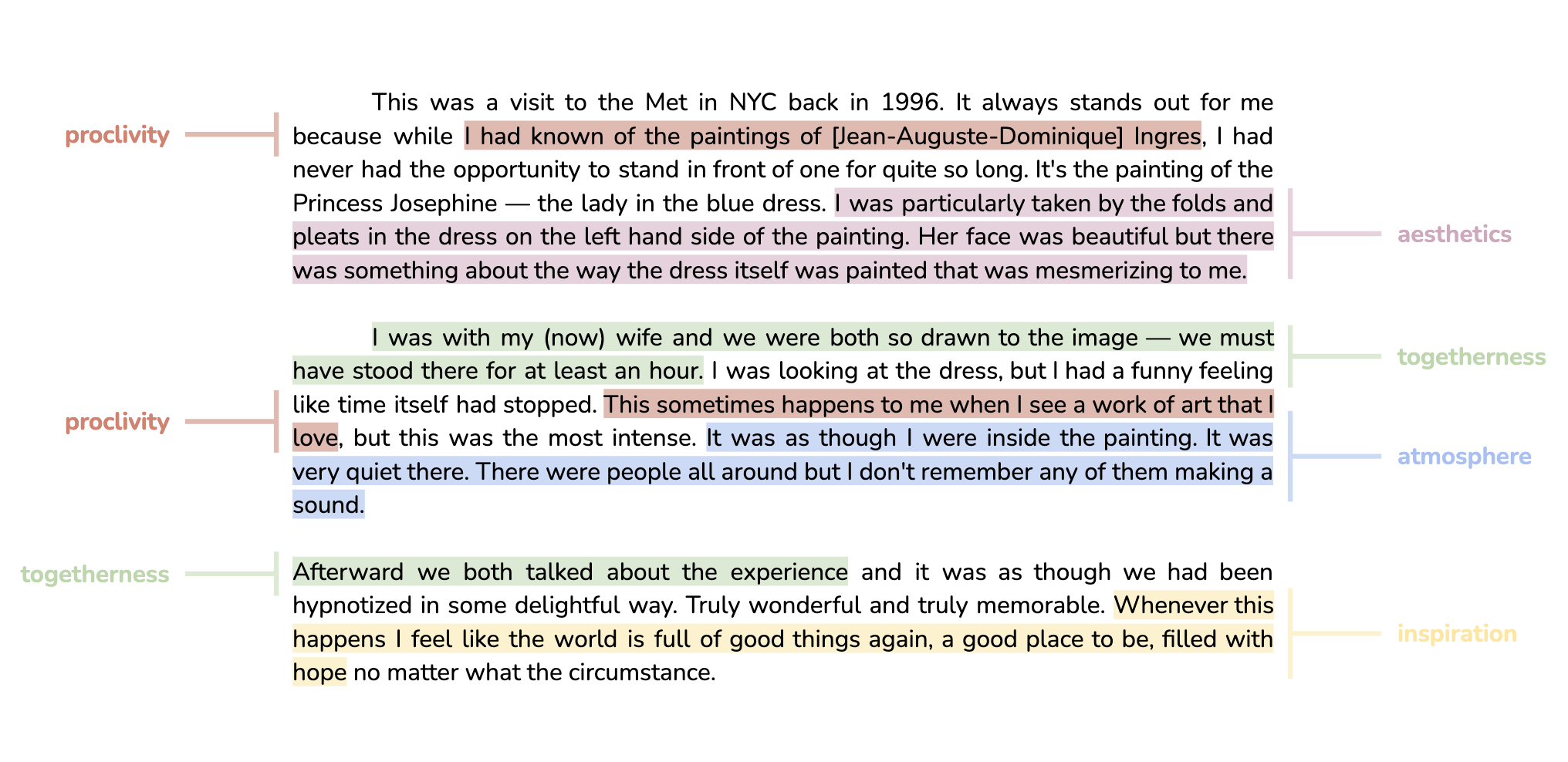

A museum visitor recounted this story, which features a number of triggers such as proclivity, togetherness, aesthetics, and inspiration.

This example demonstrates a variety of phenomena relating to meaning-making for the visitor. First, the participant emphasised in their recollection that they had a previous interest in the artist already as well as an interest in art more generally (proclivity). In other words, factors beginning before the visit itself had an important impact on the experience. Next, viewing the painting resulted in a deep aesthetic appreciation (aesthetics), which was shared with another person (togetherness). Finally, the resulting experience also led the participant to have a feeling of well-being (inspiration).

Experiences are not solely related to art and aesthetic appreciation. For example, many stories feature salient experiences from childhood that remain with visitors even after decades have passed.

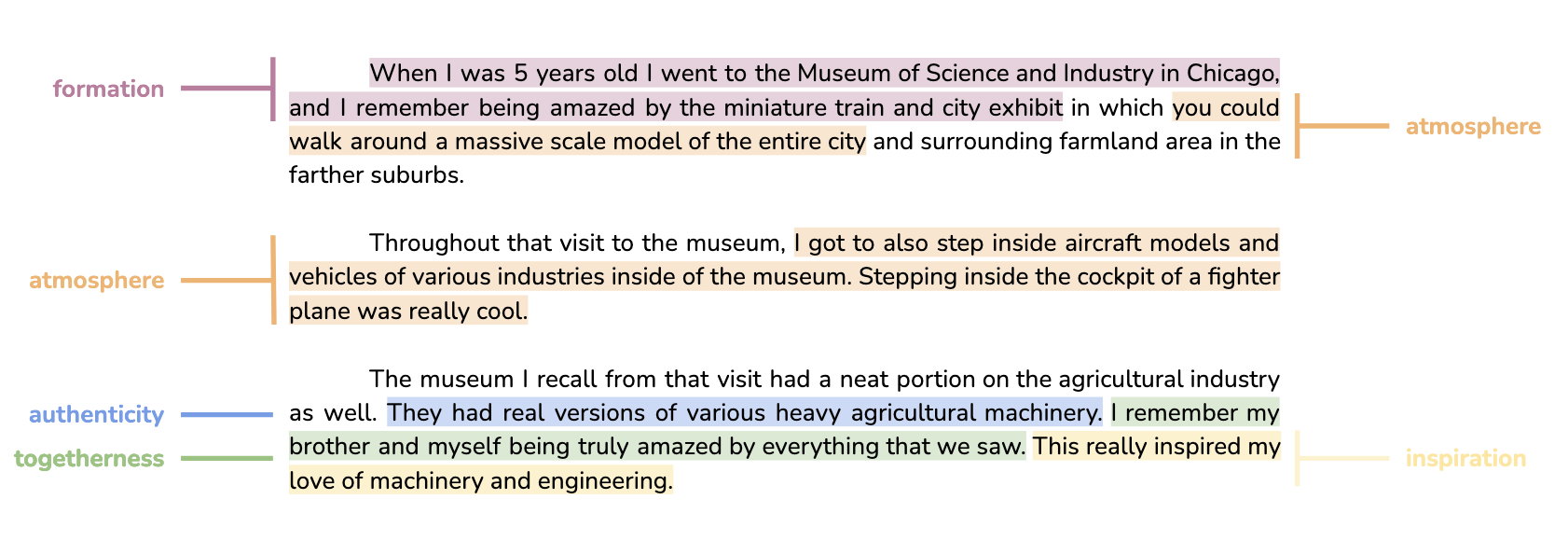

This story from a visitor’s childhood features the triggers formation, atmosphere, authenticity, togetherness, and inspiration.

In this memory, the formation trigger (meaningful experiences from childhood, or other “first times”) connects to the inspiration trigger at the end of the story, indicating that this early childhood experience inspired a love of machinery and engineering in the participant. Part of what made the visit so impactful was the ability to enter inside of the exhibits (atmosphere) and to experience objects as they really were (authenticity). Finally, this story also features the togetherness trigger, as did over 60 % of our collected data. Indeed, museums are social spaces and visiting together with friends, loved ones, or even strangers seems to deepen the experience.

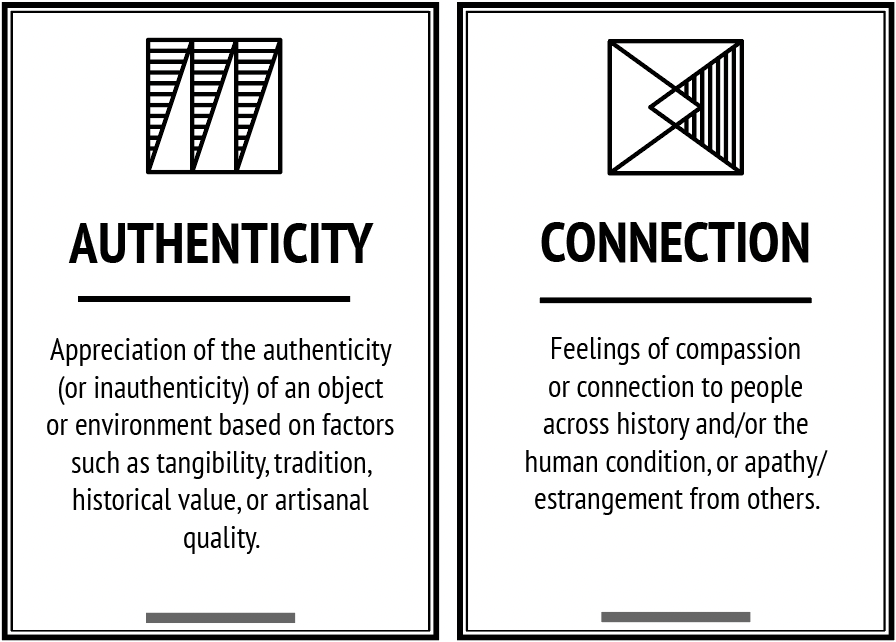

My Museum Experience (MyMuEx) trigger cards. Altogether there are 23 cards featuring individual definitions for each trigger.

Triggers are not only positive. Visitors also shared stories lamenting their boredom on the gallery floor, their bewilderment at the behaviour of fellow museumgoers, the alienation they felt when they faced racism or prejudice from museum staff, and a myriad of other negative experiences. In consideration of the complex anatomy of the museum visit, it is essential for museums to understand the good and the bad alike. To this end, we created a series of 23 cards (see above) that include the individual triggers and their definitions, both positive and negative.

On the surface, the notion of meaning is very fickle. What is meaningful for you may not be meaningful for me. However, our research suggests that meaning arises in some universal flavours and that museums can articulate their societal impact through the language of meaning. Communicating impact is more important than ever in the cultural sector and exhibitions of the future may benefit from a close consideration of meaningful triggers during their initial conception. Understanding meaning also has important implications for individuals. Through the language of meaning, we can reflect more deeply on what we personally value and how these values inform our relationship with cultural institutions going forward.

I would like to thank my colleagues at the Human-Computer Interaction Research Group at the University of Luxembourg for their support in this research, especially Dr. Vincent Koenig, Dr. Carine Lallemand, Dr. Kerstin Bongard-Blanchy, Dr. Sal Rivas, and Dr. Jasmin Niess.

Les plus populaires

- 20 juil. 2023

- 04 avr. 2024

- 27 mar. 2024

- 26 mar. 2024

ARTICLES

Articles

15 avr. 2024TAKEOVER – METAL EDITION

Articles

12 avr. 2024Veda Bartringer

Videos

12 avr. 2024