20 déc. 2021“Vagina is watching you”: The pervasive gaze of Deborah de Robertis

Using nudity as a form of protest and a tool for critical thought, Deborah de Robertis’ works have consistently challenged patriarchal structures in the art world and beyond, from her earliest pieces at art school through to her later performances in the museum space and public sphere. We sat down with the French-Luxembourgish-Italian artist to discuss the different ways in which her practice disrupts voyeuristic tendencies, inverts the painterly gaze and shakes the foundations of cultural institutions through acts of self-determined and deliberately provocative gestures of exposing her vulva.

© D. Robertis, photo G. Belvèze

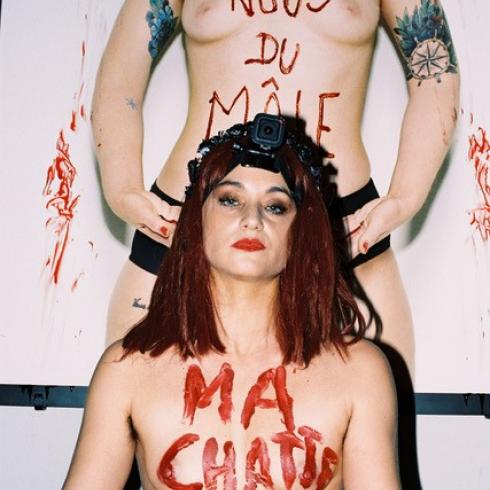

“My pussy, my copyright”

“My work has always questioned the position of women as models and the naked female body as the object of the gaze,” begins de Robertis. As early as 16, she staged her first performance for art school and adopted different positions of wax dolls in the nude. “There was already an awareness of the fact that women were routinely treated as objects in the piece,” notes the artist. Her practice of inhabiting passive female figures in order to give them a sense of agency is a key element in de Robertis’ work, as is asserting her own rights in terms of authorship and intellectual property.

Indeed, this is something she has had to fight for from the very beginning. The photographer she hired for her interpretation of the wax dolls, for instance, referred to de Robertis as the model – an object subjected to his gaze – rather than the artist in the contract he drew up. Which meant that he – the spectator – would have author’s rights on the resulting images. “That was my first argument over copyright issues with a photographer, but it certainly wasn’t the last,” she points out. She cites a later example where a photojournalist took a picture of a performance she staged during the Gilets jaunes protests on the Champs Elysées in December 2018. In the media, it was presented as a simple photograph since the journalist held the author’s rights on the image and, thus, could steer the narrative behind it. “No-one even contacted me for my point of view, instead the photographer used his privilege to invent a new story for the performance,” she observes, pointing to the problematic nature of what in French are called “droits de paternité”, the very term revealing the patriarchal system underpinning the notion of author’s rights. “What I’m fighting for are the “droits de maternité”,” she underscores.

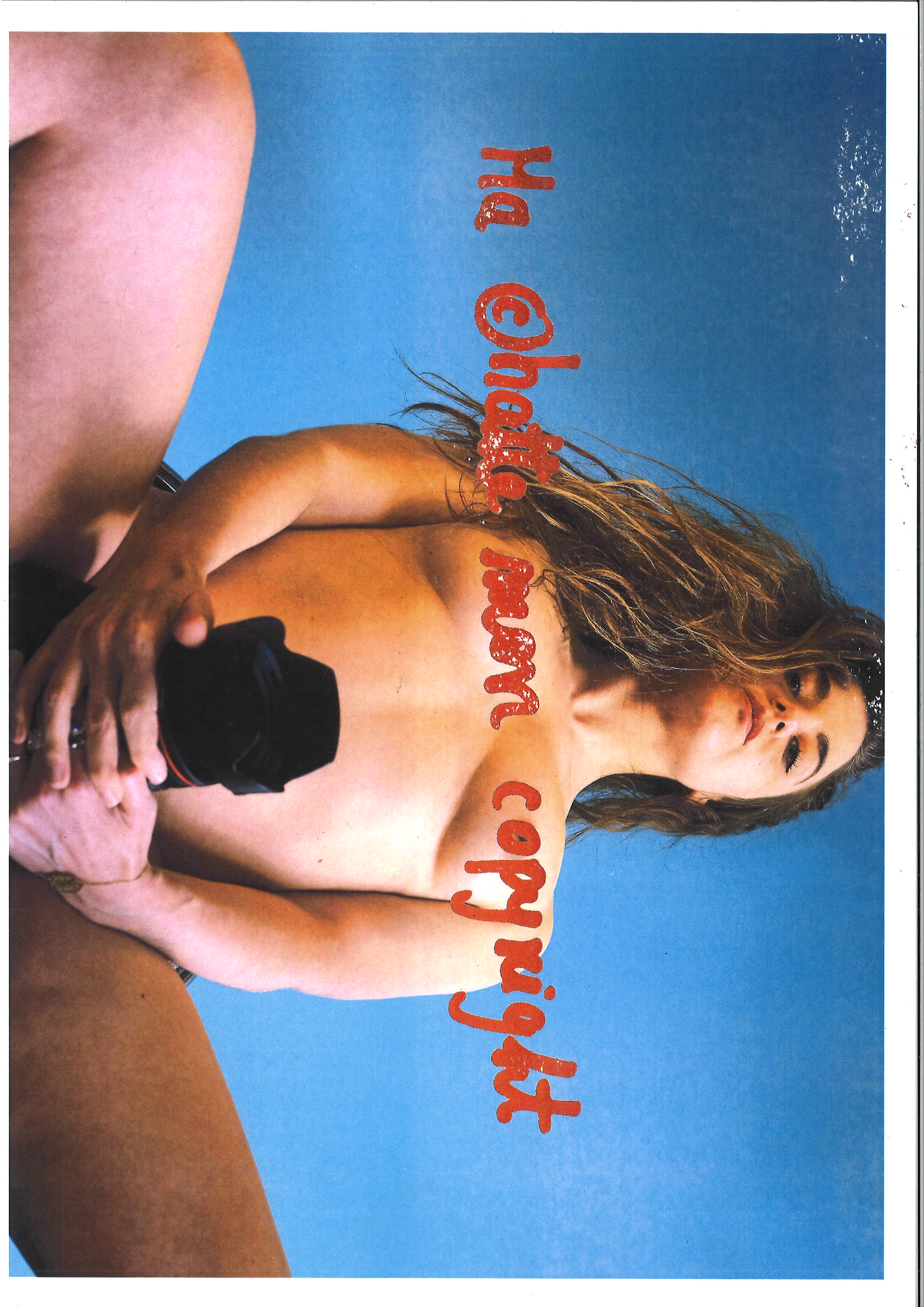

My pussy my money © D. Robertis, photo G. Belvèze

These conflicts over image rights gave rise to de Robertis’ often quoted motto “My pussy, my copyright”. As she explains: “My body belongs to me and the images I create with my body and my vulva are my intellectual property too.” An early performance staged in Brussels for her art degree entitled Modèle à la camera (2009) illustrates this well. She invited artists to photograph her as she took the position of a prostitute in a window with a camera strapped to her head to film the audience. They could take whatever pictures they liked, but they had to sign over the author’s rights to her. Thus, time and time again, the artist mimics the position of a passive female figure, yet reverses the point of view as well as challenging copyrighting conventions.

“When I open my vulva, I open my mouth”

After repeated encounters with powerful male figures in the art world who were more interested in de Robertis’ actual genitals rather than the concept of the vulva she presented in her pieces, the artist started a series of photographs entitled Mémoire d’origine whilst still at art school. “I was so sick of hanging around men who took advantage of their position and were never going to exhibit my work, so I started to expose myself in galleries and exhibitions. I quite literally penetrated the art world with my vagina.” Her first museum performance in response to Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde at the Musée d’Orsay was the logical continuation of her photo series. In Le mirroir de l’origine (2014), she sits down in front of the painting, gold dress hiked up, and holds open her labia, Schubert’s Ave Maria playing in the background. De Robertis describes the piece as a cry of rage and an act of emancipation, noting that “I often say that when I open my vulva, I open my mouth.” Opening her vagina also exposes what the artist calls “the eye of the female genitalia” whose gaze denounces museum structures’ hypocrisy; why is it acceptable to exhibit female genitalia in a painting by a man, but not in real life? “The institutions know that they’re going to be exposed. Being seen by the vagina unsettles them,” states di Robertis.

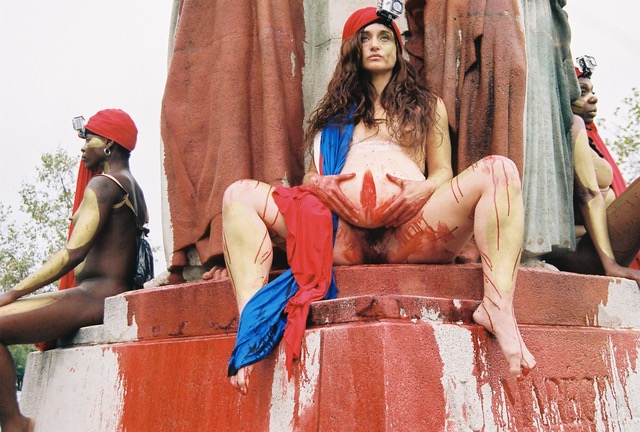

Le viol du pouvoir © D. Robertis, photo Dorothée Sarah

The choice of painting was, of course, strategic. A reference in the history of art, L’Origine du monde depicts a close-up view of a naked woman’s vulva. The model’s head is cropped out of the frame, leaving a passive body that the viewer can penetrate at leisure. In putting a face to the body, de Robertis instils the figure with a female subjectivity and prevents this symbolic rape by way of the gaze. Her piece can, thus, be seen as a response to the absence of the female perspective in art history, what she refers to as a gap or a blind spot. Seeking to redress the balance, the artist reverses the point of view and speaks out against women being portrayed as sexual objects for the pleasure of the male viewer.

Her subsequent performances follow the same line of reasoning, symbolically violating the museum space in order to upend the power dynamics at play; “I exploit these places for my own purposes and use their prestige to write myself into art history,” the artist observes. For example, in her reinterpretation of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa at the Louvre in 2017, she penetrates the protective barrier separating museum visitors from the painting and takes her seat right in front of the painting before exposing her genitalia to the audience. During the lawsuit that followed de Robertis’ performance, the Louvre insisted that related images and footage should be deleted from all platforms. “Not because of the nudity, but because the museum didn’t want me to make commercial use of the material captured on site,” she notes. In this sense, her work also seeks to invert the symbolic theft that cultural institutions have been committing all along by monetising female images by male artists such as the Mona Lisa and countless other female figures. In the words of de Robertis: “Now it’s the vulva that steals from the patriarchy.”

Le viol du pouvoir © D. Robertis, photo G. Belvèze

Blood for blood

De Robertis does not limit herself to critiquing power relations in the museum space, however. The artist’s latest performance Le viol du pouvoir (2021) saw her and five other women take their places on the historic statue of Joseph Gallieni on Paris’ place Vauban in late September. Gallieni played an active role in the expansion of France’s colonial empire at the turn of the 20th century and was notorious for his brutal tactics, including the massacre of the Menalamba movement in Madagascar. Posthumously honoured with the title of “maréchal de France”, a statue in his name stands in the middle of the French capital. With its phallic structure quite literally supported by four women at its base, the statue is a clear symbol of patriarchal and colonial oppression, “a white penis dressed up in bronze”, as de Robertis puts it.

In an attack on the state from the inside out, the six performers dressed as the Marianne – the symbol of the French Republic – sat with their backs to the likeness of the marshal and soaked the statue in blood flowing from their nether regions in a gesture of silent protest. As one of the performers, Tatiana Bongonga, states, “People say that we defaced and soiled the statue, but I see this menstrual blood as cleansing and purifying. It tells the truth. It shows all the blood that has flowed.” Bongonga also notes that she participated in the performance as a way of letting go of mental blocks linked, amongst other things, to her identity as a mixed-race person that she had internalised growing up; “I felt I needed to take a stand and exercise my right to express myself as a woman of colour, but first and foremost as a human being.” An arresting commentary on the power structures that govern and oppress French citizens to this day, Le viol du pouvoir will live on in the form of a video piece the artist is currently working on.

Whether she’s performing at the Louvre or on the Champs Elysées, Deborah de Robertis always represents women as “watching bodies” and creates artworks that evade simplistic readings. Indeed, she is quick to caution viewers to not read her works as acts of militant activism that have to be understood straight away. Her pieces are multi-layered constructs and can’t be reduced to a single meaning. “If men have the right to produce “complex” work that allows for multiple readings, why should it be any different for feminist artists? The intellectual standards should be as high for women as they are for men,” concludes de Robertis.

Les plus populaires

- 26 juin. 2024

- 28 juin. 2024

- 05 juil. 2024

- 04 juil. 2024

ARTICLES

Videos

26 juil. 2024TAPAGE avec Ruth Lorang

Articles

22 juil. 2024Le fabuleux destin de Raphael Tanios

Videos

19 juil. 2024